Mount Everest is known for its breathtaking beauty and is the ultimate destination for mountaineers. But it also holds some of the most tragic stories in history. High on the icy slopes of the mountain on the Northeast Ridge, lies one of the most haunting figures in mountaineering history, Everest Green Boots.

Curled inside a shallow limestone cave at an altitude of 8,500 meters, his green boots have marked this spot for nearly three decades. To some, the Green Boots Mt. Everest is a tragic symbol of the deadly allure of the world’s highest peak. For some, he remains a silent landmark, who is passed by hundreds of climbers every year in their conquest of the Everest summit.

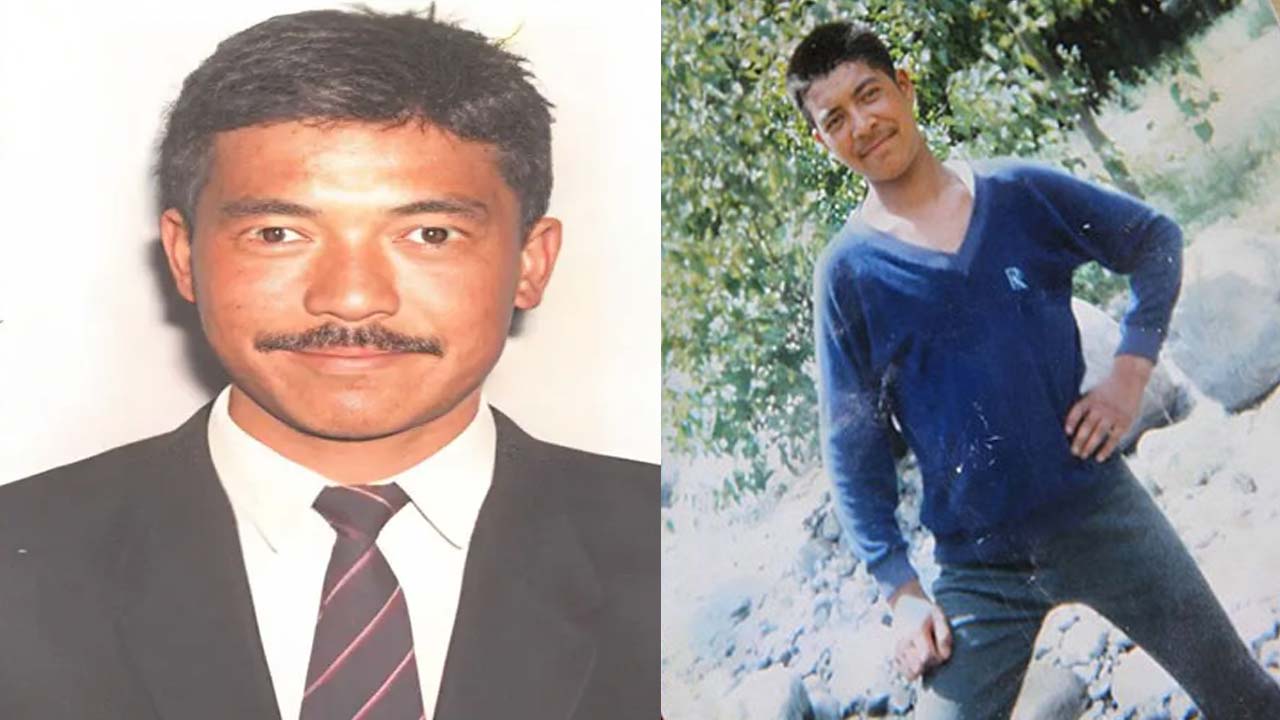

Although his identity was never officially confirmed, Green Boots on Everest is widely believed to be Subedar Tsewang Paljor. He was a 28-year-old Indian mountaineer who lost his life in the 1996 Everest blizzard, one of the deadliest disasters in Everest Expedition history that took the lives of eight climbers from different expedition teams.

Since then, Everest Green Boots body remains frozen on the North Col route, preserved by the snow and untouched by time. This is not just a grievous story of a climber who never made it home, it is a story of how a final resting place of a man with a heart full of dreams became one of the most recognized and debated topics in the world of high-altitude mountaineering.

Who is Green Boots on Everest?

‘Everest Green Boots’ is the nickname given to a mountaineer whose body became one of the most recognized and haunting landmarks on Mount Everest. Green Boots, one of the most distinguished dead bodies on Everest, remained curled in a limestone alcove on the Northeast Ridge route.

For years, Everest Green boots’s presence was unavoidable. He lay along the main climbing route where nearly every climber ascending from the north side passed. The climbers scaling the tallest peak in the world acknowledged this heartbreaking landmark as a chilling symbol of the danger involved in the Everest expedition.

The Everest Green Boots body is widely believed to be that of Subedar Tsewang Paljor, who was a 28-year-old mountaineer from Ladakh, India. Paljor was born on 10th April 1968 in a small village called Shakti in Ladakh.

He was the eldest child in a middle-class farming family. From childhood, Paljor was shy, kind and compassionate. He had a deep respect for nature as he grew up in an environment shaped by the Himalayas.

As the eldest son, he felt pressure to provide for his family, which was struggling financially on their modest farm. So, after completing his 10th level education, Subedar Tsewang Paljor quit school and applied for the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP).

This armed force was created in 1962 in response to increasing hostilities from China. Every single soldier serving in the ITBP armed force specialized in the high-altitude landscape. It was a necessity for the force as they had to operate in the border that stretched across the Himalayas.

Paljor, who grew up playing and exploring the high-altitude landscape, made the cut in the armed force. Tashi Angmo, Tsewang’s mother, was very supportive of his position in the army. But Paljor sensed that she wouldn’t be supportive of his expedition to the tallest peak in the world.

Thus, when he was selected for the elite group of climbers who were aiming to become the first Indians ever to summit Mount Everest from the north side, Tsewang Paljor didn’t reveal it to his mother. As a matter of fact, he lied and told his mother that he was going to climb a different mountain.

The 1996 Everest Disaster

Before he became known across the world as Everest Green Boots, Subedar Tsewang Paljor’s career had already included many successful summits of other smaller peaks. He had a whole shelf with certificates and awards that portrayed his mountaineering legacy.

His mother, Tashi Angmo, after finding out that her son had signed up for a dangerous expedition, implored her son not to go. But in response, Paljor said, ‘he had to’. According to his family, the ITBP soldier must have thought that if his expedition was successful, it would bring benefits for his family.

Paljor’s brother, Thinley Namgyal, met him in Delhi just days before he was about to leave for the expedition. According to his brother, who is a monk, Tsewang Paljor had passed his health exam and was really excited for the climb.

He wasn’t nervous at all; he was really happy about all of this, stated his brother Thinely to reporters.

Then, the tragedy struck, and Thinley was the last family member to see Paljor alive.

The spring climbing window of 1996 saw one of the deadliest seasons in Everest’s history. This tragic season was marked by chaos, miscommunication and unforgiving weather on the mountain. On 10th May 1996, a deadly blizzard hit the mountain slopes, which took the lives of eight climbers from different expedition teams.

One Step from Glory, One from Death: The Curse of Summit Fever

Initially, the Everest expedition was proceeding smoothly for Tsewang Paljor’s team. Commandant Mohindra Singh was leading the expedition team of Paljor, Tsewang Smanla and Dorje Morup. Harbhajan Singh also supported the expedition team as a deputy team leader.

According to Commandant Singh, Everest Green Boots, Tsewang Paljor, was a very talkative and child-like person. He wanted to do a lot of things in his life. Paljor loved to attempt climbing difficult rocks and was always volunteering to take on difficult jobs.

The ITBP soldier was very helpful to everyone around him. All three climbing members, Paljor, Smanla and Morup, were from Ladakh and had proven themselves in the field. So, Commandant Mohindra Singh was confident about all of his climbers.

However, the expedition was marked by ‘mistake after mistake’ and the climbers failed to follow clear instructions. The problem started on the morning of 10th May when the ITBP expedition team was delayed by a strong wind. They also had overslept, as the summit push usually starts at around 2:00 AM, aiming to descend to camp by 2:00 PM.

The climbers had not set out of Camp VI (8,230m/ 27,001ft) till 08:00 in the morning. They had planned the summit push initially at around 03:30 AM. So, as the expedition team had a delayed start, they decided to move further up the mountain to fix ropes rather than pushing for the summit right away.

Fixing ropes on the mountain would guarantee a safe descent even in the dark for the climbers inside the death zone. The ITBP team, including Green Boots Mt Everest, had made significant progress by 2:30 PM. Expedition leader Mohindra Singh had given a strict order to the climbers to turn around at 2:30 or at the latest 3:00 PM.

If you are not familiar, there is a 2 o'clock rule Mount Everest. It is a safety guideline that dictates climbers should turn back by 2:00 PM from the summit push, regardless of their progress on the slope.

This rule has been set taking afternoon weather decline into consideration, limited oxygen and strength for the return trip and safety as well as visibility. Harbhajan Singh, who was following the three Ladakhi climbers, was lagging far behind.

Being mindful of the direct order from Commandant Mohindra Singh and 2 o'clock rule Mount Everest, Harbhajan decided to return. He signaled the three Ladakhi climbers to stop and return to the camp. But, it was unclear whether they didn’t see the signal or ignored him.

The climbers continued with their ascent. Harbhajan Singh, who was suffering from frostbite, had no choice but to return to safety at Camp VI. He watched the three climbers pushing for the mountain peak as he descended.

At around 3:00 PM, Commandant Mohindra Singh was awaiting news of his expedition crew at Advanced Base Camp, received a message from Smanla. The message on the walkie-talkie was

“Sir, we are heading towards the summit.”

Singh was taken by the message and told Tsewang Smanla to return back to the camp as the weather conditions were starting to deteriorate. However, Smanla was serious about the summit push and was not to be dissuaded. He reported that all three men felt fit and motivated and the summit push was about an hour away.

The expedition leader told the climber not to be overconfident and to make a safe descent to the camp as the sun was going to set. Tsewang Smanla, shrugging off the warning, handed the radio to Tsewang Paljor.

Then, as Paljor was making a request, “Sir, please allow us to go up!” in a voice full of pride, the radio connection was cut off. It was around 5:35 PM that the Commandant Singh heard back from his men. Smanla announced that he, Paljor and Morup had successfully conquered Mount Everest from the northern side.

A flood of relief and excitement washed over the expedition leader. He stressed the urgency of returning back to camp for the climbers as soon as possible. Then, the news of triumph echoed across the camps on the mountain and home.

However, the celebration at the camp was short-lived. The weather condition on the mountain, which was slowly deteriorating, broke and spiraled across the mountain slope. The deadly blizzard of 1996 had arrived.

The blizzard cloaked the slopes of the mountain with the fury of snow and harsh high-altitude wind. This infamous 1996 blizzard took the lives of eight climbers from different expeditions on both the north and south sides of the mountain.

Ethical and Cultural Reflections

As the news of the blizzard reached Commandant Singh at the Advanced Base Camp, keeping the fear of the worst at bay, he told himself that his men would be fine. The three Ladakhi men had dealt with the worst weather in the past.

So, he believed if they hustled, they could be at Camp VI by midnight. However, the climbers of the ITBP never made it safely to the camp. By around 8:00 PM on the fateful day of Paljor, Smanla and Morup’s ascent, Commandant Singh could no longer contain his worry.

He decided to approach a Japanese commercial climbing team from Fukuoka for help. Two climbers from the Japanese expedition team, Hiroshi Hanada and Eisuke Shigekawa, were planning for the summit push on that night.

With the help of a Sherpa who spoke Japanese, Commandant Singh relayed the seriousness of the issue and asked for aid from his expedition team. Then, the Japanese expedition leader radioed his team at Camp VI about the situation.

The Japanese expedition leader also assured Commandant Singh that his team would do all they could if they encountered the stranded ITBP climbers during their summit. According to Singh, the Japanese ensured that they would take this crisis as their own.

However, the Japanese expedition team didn’t deliver what they had promised. By 9:00 AM the next morning, on 11th May, the storm had died down and the Japanese team proceeded further with their summit plan. The leader of the team informed Commandant Singh that two of the climbers had encountered Dorje Morup.

Morup was found lying in the snow and frostbitten. The Japanese climbing team had helped him clip to the next fixed line. But, they continued with their summit without helping him. When Commandant Singh heard this, he was shocked to his core.

Again, about two hours later, under the clear and blue skies, Japanese climbers, Hiroshi Hanada and Eisuke Shigekawa, passed Tsewang Paljor and Tsewang Smanla. But they didn’t stop to help the climbers.

However, the Japanese expedition team denied this version of the event and even called it a baseless accusation. They held a press conference in Japan stating official reports that the two Japanese climbers, Hiroshi Hanada and Eisuke Shigekawa, were never informed about the Indian climbers in peril.

According to the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation’s climber’s code of ethics,

“helping someone in trouble is of absolute priority over reaching the goals set on the mountains”

Many take it to heart; it is possible to attempt the summit again, but a lost life never comes back. But, for some, they still abide by ‘everyone should look after themselves’ even if helping is possible. And there is also the practice of ‘not my team, not my problem’, which seriously questions the ethics of climbers who value a goal more than a life.

Where is Green Boots on Everest? Is Green Boots Still on Everest?

The body of Everest Green Boots lies on the main Northeast Ridge route to the summit of Mount Everest from the Tibetan side. His body lies in a small limestone cave along the trail and at an elevation of about 8,500 meters (27,887 feet).

Tsewang Paljor, later known as Green Boots Mt Everest took his last breath within the notorious Everest Death Zone. The ‘Death Zone’ on Mount Everest refers to an altitude above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet) where the amount of oxygen in the air drops so low that it can’t sustain a human life for an extended period.

This cave, which is named ‘Everest Green Boots Cave’, is situated right beneath the summit on the final stretch. Every climber who is ascending Mount Everest from the North Col route must pass this route. Thus, for many years, Green Boots’s frozen body became an eerie landmark, toward and on the descent from the top of the world.

The Mount Everest Green Boots picture, where Paljor is in a curled-up posture with his green boots sticking out of snow, became a vivid and haunting memory among the mountaineers and non-mountaineers alike.

Over the years, his presence on the North Col climbing route became so familiar that the mountaineers began to use him and his resting cave as a grim reference point. For many climbers, passing Everest green boots, or sometimes also referred to as Everest green shoes, was a stark reminder that even the strongest and experienced are not immune to the mountain’s wrath.

How Long Has Green Boots Been on Everest?

Everest Green Boots body has remained untouched for 29 years on the North Col Ridge, the main climbing route from the Tibetan side. His body was preserved in the extreme cold without decomposition. However, in 2014, some climbers reported that his body was missing from the limestone cave, where he was resting, undisturbed.

So many started to ask questions about was Green Boots removed from Everest? During the period, it was speculated that the body of the green boots might have been removed by the climber scaling the mountain. Many believed that the climbers might have buried or relocated his body out of respect or to reduce the psychological impacts on future climbers.

When this news came out, some believed the body of the green boots might have been buried by shifting snow or rockfall, temporarily concealing him from plain sight.

However, his body re-emerged on the mountain slope, the same spot where he was previously resting in around 2017. His body became visible as the ice and snow covering his body shifted. That means, as of now, green boots has been lying on the icy slopes of Mount Everest for 29 years.

The enduring presence of green boots on Everest is more than a story of tragedy; it is a stark symbol of the unforgiving nature of the mountain. For nearly three decades, his dead body on the North Col route has remained a chilling reminder of the risks climbers take during the pursuit of their dream.

Green Boots of Mt Everest has become a history of the mountain, not by choice, but by circumstances. Paljor remains forever frozen in time, at the edge of the world.

Green Boots and Sleeping Beauty Mount Everest

The highest peak on the planet holds many stories of success, survival and sorrow. But, there are only a few that are as haunting or as deeply etched into the collected memories of climbers and non-climbers like Green Boots and Sleeping Beauty on Mount Everest.

Although Mount Everest sleeping beauty and green boots Mt Everest died on separate expeditions and in different years, their bodies came to rest on the same mountain slope, visible, frozen and unfortegable.

Green boots died in the infamous 1996 Everest disaster while descending on the Northeast Ridge. Just two years later, in 1998, the mountain claimed the life of another climber, Francys Arsentiev, who was later known as Everest Sleeping Beauty.

Both became the unintended symbols of Everest’s deadly reality and mountaineering history. They didn’t just symbolize death at high altitude, but also the deeper emotional weight of climbing, where rescue is nearly impossible and where help may never come.

There is a painful irony in how Green Boots and Sleeping Beauty on Mount Everest, once full of ambition, hope and unyielding dreams, became unmoving milestones for those who followed. Their deaths have stirred debates about ethics, responsibility, respect and humanity in high-altitude mountaineering.